The U.S. Department of Labor building in Washington, D.C.

The Washington Post | The Washington Post | Getty Images

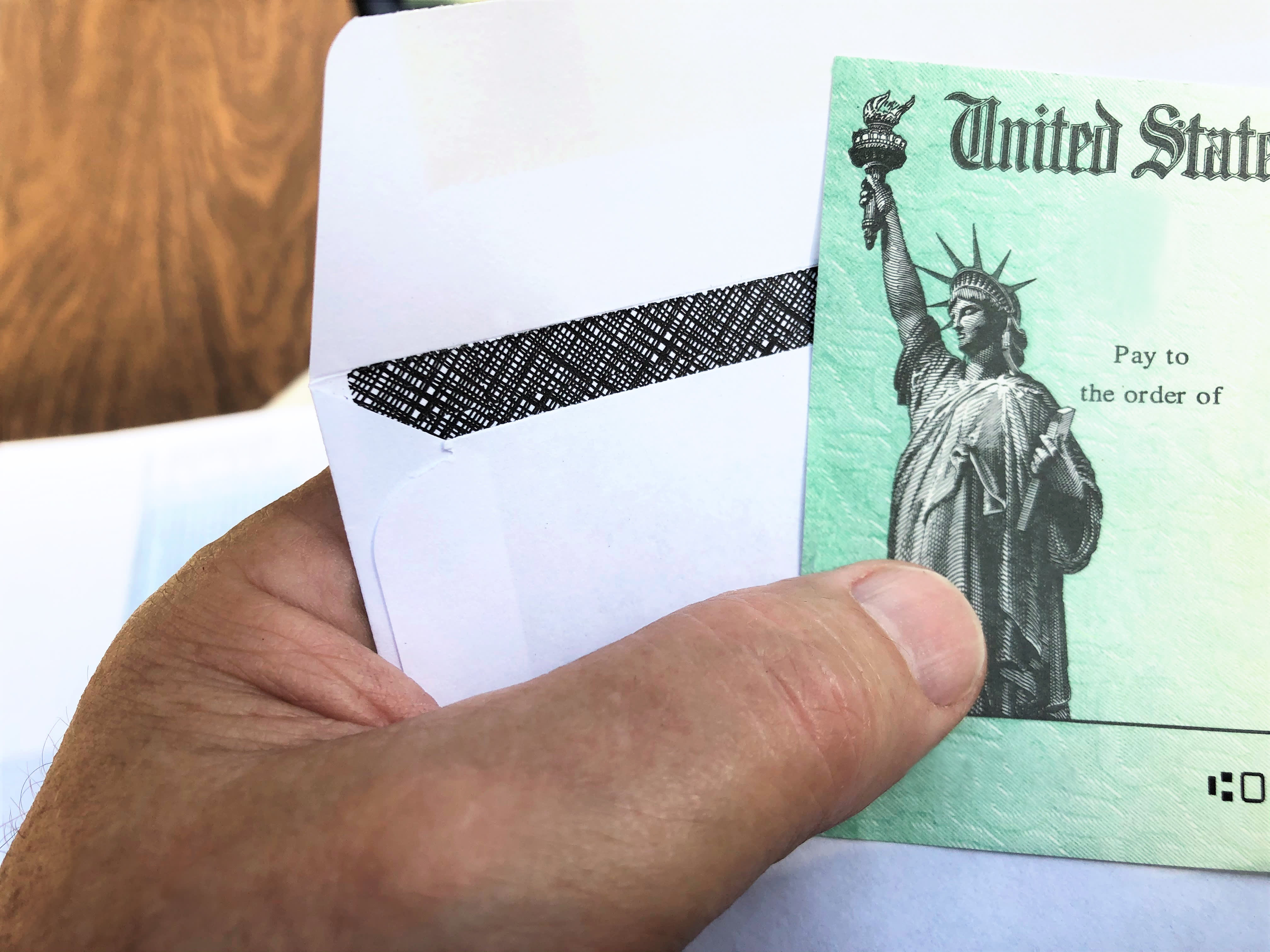

There’s a ‘tsunami’ of rollovers to IRAs

IRAs held about $11.5 trillion in 2022, almost double the $6.6 trillion in 401(k) plans, according to the Investment Company Institute. More than 4 in 10 American households — about 55 million of them — own IRAs, the group said.

The bulk of those IRA assets come from rollovers.

About 5.7 million Americans rolled a total $618 billion to IRAs in 2020 alone, according to IRS data. That’s more than double the $300 billion rolled over a decade earlier.

The figure is also seven times larger than the share of money contributed directly to IRAs. In 2020, 74% of new pre-tax IRAs (also known as “traditional” accounts) were opened just with rollovers, ICI said.

There’s a “tsunami of assets” moving from workplace plans to IRAs, Phyllis Borzi, who led the Labor Department’s Employee Benefits Security Administration during the Obama administration, said during a webcast last month.

While there are pros and cons to rolling money to an IRA, one potential drawback is that the accounts tend to come with higher fees than 401(k) plans. For example, investors who moved money to an IRA in 2018 would lose about $45.5 billion to fees over 25 years, according to Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan research group.

And most recommendations made by brokers, insurance agents and others to roll over money to an IRA aren’t subject to a so-called “fiduciary” standard of care — meaning investors may not be getting advice that’s in their best interests, Reish said.

This is what the Labor Department will likely tweak, attorneys said.

‘Game changer’: Rollover advice may be ‘fiduciary’

Borzi, the former head of EBSA, had spearheaded a sweeping Labor Department effort to rewrite “fiduciary” rules in the Obama era. Those rules aimed to clamp down on conflicts of interest among brokers and others who make investment recommendations to retirement savers.

However, the rule was killed in court.

Now, the Labor Department is trying again, though its rule likely won’t be as far-reaching, experts said.

It submitted a proposed rule — called “Conflict of Interest in Investment Advice” — to the Office of Management and Budget in September. The OMB has 90 days to review the rule, Borzi said, after which the Labor Department would issue its proposal publicly.

Based on recent legal clues, attorneys expect the Labor Department will seek to raise the bar on all rollover advice provided by the financial ecosystem.

“That’s a game changer,” said Andrew Oringer, a retirement law expert and partner at The Wagner Law Group.

Critics think a new rule would do harm, however.

Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-La., and Rep. Virginia Foxx, R-N.C., sent a letter to the Labor Department in August saying its efforts were “misguided” and risked creating confusion in the marketplace, unwarranted compliance expenses and instability for retirement plans, retirees and savers.

It may be two years or more before a final rule takes effect, due to the typical length of the regulatory process, Borzi said.

There are legal loopholes for rollovers

Here’s why a new rule would be a big deal.

There’s currently a hodgepodge of rules governing how advisors, brokers, insurance agents and others can give financial advice to retirement savers. Different actors are beholden to different rules, some looser than others.

The fiduciary protections for 401(k) investors are generally the highest known to law, attorneys said. They’re governed by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974.

That generally means investment advice must be given solely in investors’ best interests. Advisors must set aside their own self-interests, and can’t make recommendations to buy a fund, annuity or other investment that pays them a higher commission at the expense of an investor, for example.

It may not cause fewer rollovers, but it will almost certainly cause more thoughtful rollovers.

Fred Reish

partner at law firm Faegre Drinker Biddle & Reath

The singular focus on investors’ best interests “is an extremely significant difference” relative to other investor protections, Oringer said.

However, due to loopholes, rollover advice generally falls outside the purview of those protections, attorneys said.

But the Labor Department may close those loopholes and subject all rollovers to ERISA’s protections.

“All of a sudden, I’d have to care about your best interests when I try to get you to do that rollover,” Oringer said of financial firms and their agents. “That completely changes the way in which I have to behave.”

Among the other big changes: ERISA protections would give investors the right to sue someone in court for bad rollover advice, Reish said.

Currently, that private right of action generally doesn’t apply to investment advisors, brokerage firms, insurers, banks or trust companies — only their respective regulators (and not individual investors) can enforce their rules, Reish said.